We Are a Chorus

- Jun 21, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Apr 25, 2022

By Lola Olufemi.

The struggle is long and requires much from those who wish for more liveable worlds. Feminist thinking offers us a challenge; it pushes us to think beyond the limits of the given – all we have been told is impossible. Feminism is a tool, a frame, an analytic that we can use to destroy the restraints that structure this world. It argues that we deserve to live well and that we might be able to craft a world where everyone is free from harm, where exploitation and extraction do not underpin our relations or determine our interpersonal interactions. It provides an answer to the problem of capitalism, the problem of racism, the problem of gendered violence, disablism and homophobia.

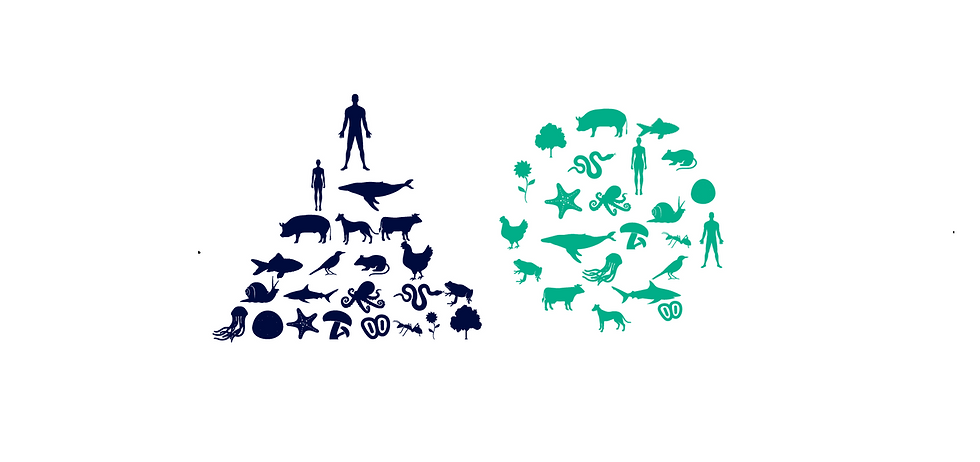

The feminist project has always been heavily tied up with imagining – feminist thinkers have needed an escape from the miserable conditions they have been subjected to and a way to contend with the failures of the promises made by the valorisation of certain male thinkers. Feminist thinking rejects the cult of the individual in favour of an understanding that our liberation will always be plural. It will always contain many routes, a multitude of conflicting ideas that clear a path for understanding how we have been forced to live and how we can work to transform these conditions. It is Saidiya Hartman’s idea of ‘the chorus’ – an amorphous multitude that ebbs and flows. Understanding the rhythms of political movements and demands is what feminism looks like in action. We are a chorus. We reject a die-hard allegiance to individual thinkers in favour of the collective. Often we have been maligned by certain parts of the left, accused of being identitarians, accused of dividing movements when really we have sought to expose how any refusal to acknowledge the multipronged consequences of exploitation will always ensure that our political projects are doomed for failure.

Feminists have insisted that our burdens are multiple. We cannot talk about work and the chains of wage labour without acknowledging how those chains have tied some of us to the home, the nuclear family, the private sphere and domestic servitude. Some of us are workers and mothers, some of us are black workers, some of us are trapped because we cannot work at all. A poster from the Red Women’s Workshop from 1983 famously reads “Capitalism Depends on Domestic Labour” as women stand around a conveyer belt. Feminism might be seen as the answer to the problem of metanarratives. By understanding gender as one of the many rubrics we use to analyse the world, we accept the premise that liberation is not a one-time event and it cannot and will not be ushered in uniformly. It is going to be chaotic and messy and it is going to require us to rethink our comrades, those people that we call brother and sister and lover, it is going to require us to come up with new names and build communities of care where we come together to support and love one another and most importantly, to strategize.

There is something that obscures this horizon. Liberals have described ‘neoliberalism’ as just another meaningless phrase. But for those interested in radical thinking and radical politics, it helps us name the condition of the societies we live in. Broadly speaking, it refers to the imposition of cultural and economic policies and practices by NGOs and governments in the last three to four decades that have resulted in the extraction and redistribution of public resources from the working class upwards, deregulated capital markets and decimated infrastructures of social care through austerity measures. It has privatised the welfare state and individualised and securitised the ways we relate to one another. Neoliberalism has had many effects on our politics, our minds and our psyches. It is what has caused the hollow feeling of emptiness that is commonplace in an increasingly atomised society. It is what dictates the social convention that we relate to our friends like soulless robots, constantly checking that we are not overstepping each other’s personal boundaries, put in place to survive. Neoliberalism has infected our feminist politics. It comes in the form of the girl boss, the women-only private members club, the feminism on sale in the tote bag, t-shirt and the badge. The focus on the individual, micro-interactions, patterns of behaviour, stereotypes. It is the imaginary figure of the woman CEO who dominates the boardroom, ‘has it all’ and does it twice as well as any man could. The hope for a woman leader no matter her political ethos, the reliance on the state and the police to provide answers to the problem of sexual and gendered violence. What is most dangerous about neoliberalism is the way it shape-shifts. It can mimic the language of liberation so well, pushing ‘women’s’ concerns to the centre, making us forget that biology is a trap.

Critical feminism is invested in creating a more just world: ending austerity, ending climate catastrophe, ending prisons, ending borders, ending the state as we know it, ending fascism. It is a project with many ends.

Remembering the radical feminist histories we belong to means refusing to capitulate: becoming problems by exposing problems in the neoliberal project. We have to start with women on the underside of capital, asking – why is it that some women’s exploitation is a natural part of other women’s achievements? We have to refuse the allure of the biological essentialism that has a viper grip on mainstream feminist politics. When white middle class cultural gatekeepers insist that the issue of our time is the supposed erasure of ‘sex-based’ rights, we have to respond by reminding them we have no cult-like allegiance to womanhood or to the violence it facilitates. We understand ‘woman’ as a category under which we gather to make political demands for our freedom and the freedom of others. It is only the possibility of freedom that matters to us. We must call this attachment to the body and chromosomal make up what it is: scientific racism in disguise. We must connect it to the encroaching fascism that seeks to swallow us all up.

We have to keep reminding ourselves and others: the police are not saviours and the state will not deliver us salvation. We have to be brave enough to proclaim that no feminism worth practicing believes in borders. When we reorientate our concerns and use feminism to uncover the way that this world is sick and makes all of us sick, it might not feel like feminist work. But it matters for those rebuilding their lives after a decade of austerity, for those sex workers that face certain death under state policies of criminalisation, those women who die because they have no routes to escape domestic violence, those women in prison, those trans women who are struggling to survive as mainstream discourses render their lives impossible, those women and children who drown between nations and those who so easily become the casualties of illegal wars and drone strikes. It matters for every person that mainstream feminism makes invisible in order to tell a neat story of linear progress and women’s achievement. What good is a parliament full of ‘female’ politicians if they step over our dead bodies to get there?

The struggle is long and requires much from those who wish for more liveable worlds. Feminist thinking offers us a challenge: we must rise to it.

Lola Olufemi is a black feminist writer and organiser from London. She facilitates workshops on feminism and histories of political organising in schools, universities and local communities. She is the co-author of A FLY Girl’s Guide to University: Being a Woman of Colour at Cambridge and Other Institutions of Power and Elitism (Verve Poetry Press, 2019). Her most recent book is Feminism, Interrupted (Pluto Books, 2020).

This article originally appeared in DOPE magazine

Comments