Nation-states are destroying the world. Could 'bioregions' be the answer?

- Matt York

- Mar 9, 2022

- 9 min read

Updated: Apr 25, 2022

By Shrishtee Bajpai, Juan Manuel Crespo, and Ashish Kothari

From the border regions of South Asia to the Amazon rainforest, people are seeking new ways to organise societies that respect humans and nature.

"Panchi nadiya pawan ke jhonke

Koi sarhad na inhe roke

Sarhadein insaano ke liye hai

Socho tumne aur maine kya paaya insaan hoke"

(Translation)

"Birds, rivers and the gusts of wind

No borders can stop them

The borders are for humans

Just think, what have we got by being human?"

Javed Akhtar, Indian lyricist

It is becoming increasingly obvious that we need to think about the problems of the climate crisis and borders together. Environmental breakdown displaces millions of people every year, while states respond by militarising their borders, causing further suffering and death.

It is no accident that climate breakdown and state borders are linked. Historically, the nation-state was born out of a logic that also saw nature – and colonised peoples – as things to be conquered and dominated. Now, from the war-torn border regions of South Asia to the Amazon rainforest, people are questioning whether sustainability can ever be achieved through the framework of nation-states. They are turning to other ways of organising society based on Indigenous worldviews and practices that respect all humans and the rest of nature.

Colonialism, capitalism and the nation-state

In the last 500 years, colonial conquests of vast regions of the earth by European and North American powers, based on the capitalist profit drive and rapid technological development, resulted in the decimation of countless cultures and communities. This includes the death of over 50 million natives in what subsequently came to be known as Latin America, devastating famines in Asia and Africa caused by policies imposed by colonisers, and the conversion of millions of hectares of natural ecosystems into commercial plantations, logging estates, or livestock ranches to feed the consumer demands of Europe and North America.

In the same period, there emerged the idea and practice of the nation-state. Though its origins and nature are diverse and complex, the centralisation of power in the hands of the nation-state was one of the bases of capitalism: in practice, capitalism is carried out through the political, legal and military institutions of nation-states. Nation-state building was supported by an ideology asserting that capitalist modernity is the only way to organise lives, and that this justifies taking over territories of Indigenous peoples and local communities for national goals like development and security. Nation-state symbols such as one flag, one language and a single identity submerge and often disrespect diverse biocultures – combined biological and cultural human environments. We must see the nation-state, capitalism and colonialism as going hand in hand.

The ideology of the colonial-industrial age stated, deludedly, that humans were separate from nature and that human progress was contingent on conquering it. After the Second World War, old forms of colonialism were defeated in most parts of the world. In their place a new ideology was needed to continue the domination of the West. This was the ideology of development, or ‘developmentality’. We might assume that the idea of ‘development’ is progressive, but we would be mistaken. Developmentality convinced the world that human progress was linked to ever-expanding material and energy growth. The ecological crises the world is facing today are largely a result of these five centuries of colonialism and developmentality.

It is in this context that there is now an intense search for radical alternatives which can meet the needs and aspirations of all peoples while living in harmony with the rest of nature.

Bioregionalism and radical democracy

In central India, 90 villages formed a mahagram sabha (federation of village assemblies) in 2017 and are asserting their decision-making over the entire region, brought together by a traditional sense of biocultural identity rather than current administrative or political boundaries. In 1999, 65 villages that were part of a river basin in the Indian state of Rajasthan, formed a people’s parliament that governed it for a decade, ignoring the administrative division of the basin. These and other examples are pointers to a radically different approach to governance: bioregionalism.

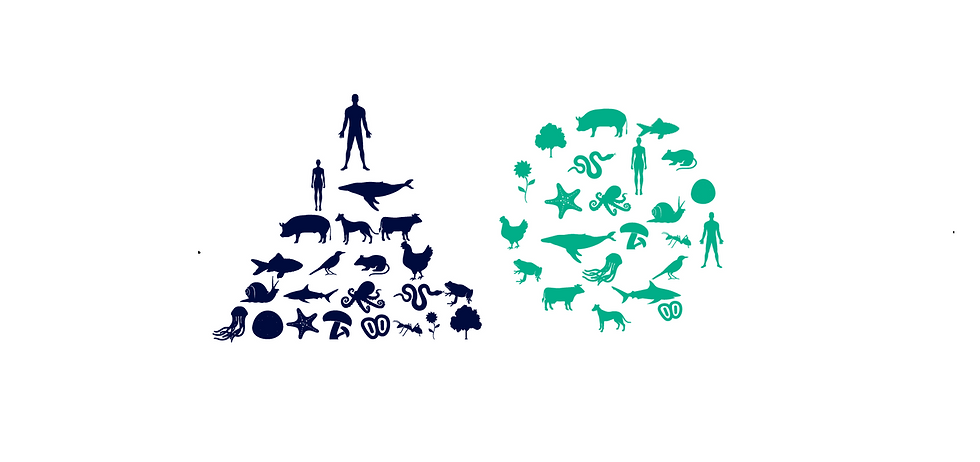

Bioregionalism is based on the understanding that the geographic, climatic, hydrological and ecological attributes of nature support all life, and their flows need to be respected. Bioregions, also known as biocultural regions, are areas with their own ecologies and cultures, in which humans and other species are rooted, actively participating at various scales beyond the immediate locale. While many current human-made boundaries disregard nature’s flows and territories – such as a mountain range or a river – many local communities and Indigenous peoples have long lived with deep understanding and respect for these. They understand the interdependence of all living beings across a landscape or seascape.

There are many examples of bioregional governance, both old and new. For thousands of years Nomadic pastoralists in Iran used large territories encompassing a diversity of ecosystems, their practices tuned to an acute understanding of which ecosystems could take how much and what kind of use. In more recent times, the Indigenous nation of Monkox of Lomerio, Bolivia, won territorial self-determination rights in 2006, and is attempting transformations in its economic, political, social and cultural life based on a life plan for the whole region. The Great Eastern Ranges project aims to protect, connect and restore habitats across a 3,600 km swathe of eastern Australia, by creating regional coordination channels among various actors. In many other parts of the world, Indigenous Peoples or other local communities are sustaining traditional landscape governance mechanisms, or creating new ones, as part of a global phenomenon now known as Territories of Life. Many of these projects cross political and administrative borders, respecting instead ecological and cultural flows and boundaries.

At their best, these bioregional projects are based in radical, direct democracy. Decision-making power is ultimately held at a local level, by which everyone is able to participate. For decisions affecting larger territories, delegates are sent to decision-making assemblies appropriate to that scale. There are close affinities between these movements and what Mahatma Gandhi called swaraj, a worldview that asserts autonomy, freedom and sovereignty, but in nonviolent ways that are responsible to the autonomy and well-being of all others.

Reimagining South Asia from a bioregional perspective

For various historical reasons including colonisation, South Asia is currently divided into several nation-states, with political borders that cut through ecosystems and cultures. For instance, the world’s largest mangrove forest, the Sundarbans, is divided by the India-Bangladesh border. The high mountains of the Himalaya and the vast desert areas in the west are divided between India and Pakistan. The great high-altitude plateau north of the Himalaya is fenced off with Ladakh on one side and Tibet (governed by China) on the other. The waters of the Indian Ocean are partly partitioned amongst India, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives.

Here is a vision for South Asia that is very different from the current reality, adapted from an essay one of us co-authored. It is part of an imaginary address to inhabitants of South Asia by one Meera Gond-Vankar, in the year 2100:

While India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Bhutan, Sri Lanka, and China still retain their ‘national’ identities, boundaries have become porous, needing no visas to cross. Local communities have taken over most of the governance in these boundary areas, having declared peace in previous conflict zones like Siachen, the Kachchh and Thar deserts, and the Sundarbans. The same applies to the Palk Strait, with fishing communities from both India and Sri Lanka empowered to ensure sustainable, peaceful use of marine areas. Greater Tibet has become a reality, self-governed, with both India and China relinquishing their political and economic domination over it. Both nomadic communities and wildlife are now able to move freely back and forth.

In all these initiatives, narrow nationalism is being replaced by civilisational identities, pride, and exchange, a kind of self-fashioned ethnicity that encourages respect and mutual learning between different civilisations and cultures. South Asia learnt from the mistakes of blocks like the European Union, with its strange mix of centralisation and decentralisation and continued reliance on the nation-state, and worked out its own recipe for respecting diversity within a unity of purpose.”

While this is a futuristic vision, some tentative pathways towards this are already being forged. In addition to the examples given above of villages coming together to democratically govern bioregions, peace-centred people-to-people dialogues are underway, such as the Pakistan-India People’s Forum for Peace and Democracy. The idea of a Siachen Peace Park in the intense conflict area between India and Pakistan has been proposed for many years, and even endorsed by former Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Transboundary conservation cooperation exists between Manas Tiger Reserve in India and Royal Manas in Bhutan, aligning with several dozen such initiatives already established around the world. But of course, given the continuing atmosphere of distrust and conflict in the region, accompanied by periodically rising hypernationalistic discourses (currently, promoted by the party in power in New Delhi), there is a long way to go for these pathways to be trod.

Shaping a bioregional approach to the Amazon Sacred Headwaters

The Sacred Headwaters region in the Upper Amazon is one of the birthplaces of the Amazon river. It spans 35 million hectares (86 million acres) in Ecuador and Peru, and is home to nearly 600,000 indigenous people from 30 nationalities, including peoples living in voluntary isolation. It is the most biodiverse terrestrial ecosystem on the planet, and represents both the hope and the peril of our times. Indigenous peoples’ struggles have kept this region largely free of industrial extraction. Studies by international organisations such as the UN, Rainforest Alliance and Hivos have demonstrated how Indigenous peoples are the best guardians of nature, especially in the Amazon bioregion.

In response to new threats from the Ecuadorian and Peruvian states to expand oil, mining and intensive agro-industrial projects, Indigenous confederations from both countries banded together to form the Amazon Sacred Headwaters Initiative (ASHI). In 2019, Sacred Headwaters made a public declaration:

We call for the global recognition of the Amazon Rainforest as a vital organ of the Biosphere. We call on the governments of Ecuador and Peru, on the corporations and financial institutions to respect indigenous rights and territories and stop the expansion of new oil, gas, mining, industrial agriculture, cattle ranching, mega-infrastructure projects and roads in the Sacred Headwaters. The destructive legacy of this model of "development" has been major deforestation, forest degradation, contamination, and biodiversity loss, decimating Indigenous populations and causing human rights abuses. We challenge the mistaken worldview that sees the Amazon as a resource-rich region where raw materials are extracted in pursuit of economic growth and industrial development…

Instead of a view of development that sees human progress as the conquest of nature, Sacred Headwaters understands the interdependence of all life across national borders. ASHI’s Bioregional Plan proposes Indigenous self-determination with effective participation of women; a highly diverse economy combining new with ancestral farming methods and food and energy sovereignty; intercultural health systems that respect gender and generational diversity; educational systems that combine formal with non-formal learning; and a thorough conservation and restoration program for the Amazon.

Making bioregionalism a reality

Bioregional approaches, encompassing radical democracy, offer communities the chance to rebuild and enhance their lives and livelihoods, free of the constant fear of conflict and violent extractive industries. In the Amazon they could help secure the ecological, economic and cultural sustenance of Indigenous nations and other local communities, at the same time providing all the local-to-global ecological benefits of the world’s largest rainforest. In South Asia, the withdrawal of armed forces and other police and paramilitary forces from land and sea would mean that the suffering such personnel go through could be eliminated, especially in the treacherous and freezing conditions of the Himalayan border areas between India, Pakistan and China. It would also mean that a substantial part of India’s US$72 billion defence expenditure could be reallocated.

This approach would also entail undoing past damages to bioregions, as far as feasible. The impacts of climate change in forms of droughts and floods are going to become worse. It is crucial to re-imagine how we govern wetlands, and entire bioregions. Some existing dams on trans-boundary rivers may need to be decommissioned, to re-establish water, ecological and biological flows. Any further damning and major diversions must be avoided. A healthy river is often a first line of defence against climate crises for communities, including its functions as it merges into the sea. A bioregional approach may also help cope with some of the worst impacts of climate change, such as the displacement of coastal communities – including a likely attempt by Bangladeshi climate refugees to enter India, which could become a huge humanitarian crisis without adequate foreplanning – or the movement of wildlife to higher altitudes.

Bioregional approaches face significant challenges, not least of which are nationalist notions that continue to support hard nation-state boundaries. And yet, the peace dialogues, transboundary conservation projects and Indigenous bioregional initiatives discussed above are sources of hope.

Another important stepping stone is the recognition of the rights of nature. In 2017, the New Zealand Parliament passed into law the Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlement) Act, which gives the Whanganui river and ecosystem legal personhood and standing in its own right, guaranteeing its “health and wellbeing”, recognising the Iwi cosmology “we are the river and the river is us”, and acknowledging that rights extend to the entire bioregion, from mountain to sea.

Close on its heels, the Uttarakhand high court in India ruled in 2017 that the north Indian rivers Ganga and Yamuna, their tributaries, and the glaciers and catchment feeding these rivers in the state of Uttarakhand, have rights as a “juristic/legal person/living entity”.

Recognising such rights could enable management and governance based on the ecological realities of the region. This also opens up the opportunity for us to alter currently dominant anthropocentric and colonial law, towards a new legal framework that respects the ‘pluriverse’ – the beautiful diversity of the world. Taken beyond the law, recognising the rights of nature opens up the possibility of articulating Indigenous worldviews of nature as a living being, even within formal institutions; and of creating a mutually flourishing future for humans and more-than-humans, where people’s lives are rooted in territories that do not have arbitrary militarised borders but are ecologically and culturally defined, open and connected.

This article was originally published in Open Democracy

1 Comment